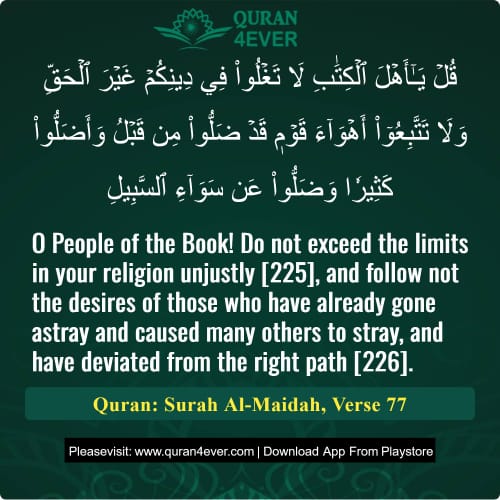

Transliteration:( Qul yaaa Ahlal Kitaabi laa taghloo fee deenikum ghairal haqqi wa laa tattabi'ooo ahwaaa'a qawmin qad dalloo min qablu wa adalloo kaseeranw wa dalloo 'an Sawaaa'is Sabeel )

77. O People of the Book! Do not exceed the limits in your religion unjustly [225], and follow not the desires of those who have already gone astray and caused many others to stray, and have deviated from the right path [226].

This command is directed at the People of the Book (Jews and Christians), warning them not to exceed limits unjustly in their beliefs or practices.

The Yahud (Jews) erred by completely rejecting the Prophethood of Hazrat Isa (Jesus, peace be upon him).

The Nasara (Christians) erred by exaggerating his status, elevating him to divinity.

From this, we learn that in religious matters, certain additions are permissible when based on sound principles—for example, Ijma‘ (consensus) and Qiyas (analogy)—but unjust excess and distortion are forbidden.

Believers should not imitate those who have deviated from the right path and misled others by following their wrongful desires.

Instead, one should follow the path of pious, righteous guides accepted by Allah. This is emphasized elsewhere in the Quran, such as:

“Then follow you their path.” (Surah Al-An‘am 6:90)

“And be with the truthful.” (Surah At-Tawbah 9:119)

Following misguided leaders only leads to corruption and deviation.

The tafsir of Surah Maidah verse 77 by Ibn Kathir is unavailable here.

Please refer to Surah Maidah ayat 76 which provides the complete commentary from verse 76 through 77.

(5:77) Say: ‘People of the Book! Do not go beyond bounds in your religion at the cost of truth, and do not follow the caprices of the people who fell into error before, and caused others to go astray, and strayed far away from the right path.[101]

101. This refers to those misguided nations from whom the Christians derived their false beliefs and ways, particularly to the Hellenistic philosophers under the spell of whose ideas the Christians had veered from the straight way they had originally followed. The beliefs of the early followers of the Messiah were mainly in conformity with the reality they had witnessed, and conformed to the teachings they had received from their guide and mentor. But they later resorted to an exaggerated veneration of Jesus, and interpreted their own beliefs in the light of the philosophical doctrines and superstitious ideas of the neighbouring nations. Thus they invented an altogether new religion not even remotely related to the original teachings of the Messiah. In this connection the observations of a Christian theologian, the Reverend Charles Anderson Scott are significant. In a lengthy article entitled ‘Jesus’ Christ’, published in the fourteenth edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica, he writes:

. . . there is nothing in these three Gospels to suggest that their writers thought of Jesus as other than human, a human being specially endowed with the Spirit of God and standing in an unbroken relation to God which justified His being spoken of as the ‘Son of God’. Even Matthew refers to Him as the carpenter’s son and records that after Peter had acknowleged Him as Messiah he ‘took Him aside and began to rebuke Him’ (Matthew, xvi. 22). And in Luke the two disciples on the way to Emmaus can still speak of Him as ‘a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people’ (Luke, xxiv. 19). It is very singular that in spite of the fact that before Mark was composed ‘the Lord’ had become the description of Jesus common among Christians, He is never so described in the second Gospel (nor yet in the first, though the word is freely used to refer to God). All three relate the Passion of Jesus with a fullness and emphasis of its great significance; but except the ‘ransom’ passage (Mark, x. 45) and certain words at the Last Supper there is no indication of the meaning which was afterwards attached to it. It is not even suggested that the death of Jesus had any relation to sin or forgiveness.

A little further on he writes:

That He ranked Himself as a prophet appears from a few passages such as ‘It cannot be that a prophet perish out of Jerusalem’. He frequently referred to Himself as the Son of Man; but while this must be maintained in face of influential opinions to the contrary, the result for our purpose is less important than we might expect, for the possible meanings of the phrase are as numerous as the sources from which it may possibly have been derived. They range from simple man’ through ‘man in his human weakness’ and the representative ‘Man’ to the supernatural man from heaven foreshadowed in Daniel. If we had to postulate one source and one meaning for the phrase as used by Jesus of Himself, it would probably be found in Psalm Ixxx., where the poignant appeal to God for the redemption of Israel runs out on the hope of a ‘son of man whom thou madest strong for thyself. The same author adds:

Certain words of Peter spoken at the time of Pentecost, ‘A man approved of God’, described Jesus as He was known and regarded by His contemporaries. He was ‘found in fashion as a man’, that is, in all particulars which presented themselves to outward observation He Appeared and behaved as one of the human race. He was made man’. The Gospels leave no room for doubt as to the completeness with which these statements are to be accepted. From them we learn that Jesus passed through the natural stages of development, physical and mental, that He hungered, thirsted, was weary and slept, that He could be surprised and require information, that He suffered pain and died. He not only made no claim to omniscience, He distinctly waived it. This is not to deny that He had insight such as no other ever had, into human nature, into the hearts of men and the purposes and methods of God. But there is no reason to suppose that He thought of the earth as other than the centre of the solar system, of any other than David as the author of the Psalms, or did not share the belief of His age that demons were the cause of disease. Indeed, any claim to omniscience would be not only inconsistent with the whole impression created by the Gospels, it could not be reconciled with the cardinal experiences of the Temptation, of Gethsemane and of Calvary. Unless such experiences were to be utterly unreal, Jesus must have entered into them and passed through them under the ordinary limitations of human knowledge, subject only to such modifications of human knowledge as might be due to prophetic insight or the sure vision of God.

There is still less reason to predicate omnipotence of Jesus. There is no indication that He ever acted independently of God, or as an independent God. Rather does He acknowledge dependence upon God, by His habit of prayer and in such words as ‘this kind goeth not forth save by prayer’. He even repudiates the ascription to Himself of goodness in the absolute sense in which it belongs to God alone. It is a remarkable testimony to the truly historical character of these Gospels that though they were not finally set down until the Christian Church had begun to look up to the risen Christ as to a Divine Being, the records on the one hand preserve all the evidence of His true humanity and on the other nowhere suggest that He thought of Himself as God.

The same author also observes that:

He proclaimed that at and through the Resurrection Jesus had been publicly installed as Son of God with power; and if the phrase has not wholly lost its official Messianic connotation, it certainly includes a reference to the personal Sonship, which Paul elsewhere makes clear by speaking of Him as God’s ‘own Son’ . . .

It may not be possible to decide whether it was the primitive community or Paul himself who first put full religious content into the title ‘Lord’ as used of Christ. Probably it was the former. But the Apostle undoubtedly adopted the title in its full meaning, and did much to make that meaning clear by transferring to ‘the Lord Jesus Christ’ many of the ideas and phrases which in the Old Testament had been specifically assigned to the Lord Jehovah. God ‘gave unto Him that name that is above every name – the name of “Lord”‘. At the same time by equating Christ with the Wisdom of God and with the Glory of God, as well as ascribing to Him Sonship in an absolute sense, Paul claimed for Jesus Christ a relation to God which was inherent and unique, ethical and personal, eternal. While, however, Paul in many ways and in many aspects, equated Christ with God, he definitely stopped short of speaking of him as ‘God’.

In another article in Encyclopaedia Britannica (xiv edition), under the title Christianity’, the Reverend George William Knox writes as follows about the fundamental beliefs of the Church:

Its moulds of thought are those of Greek philosophy, and into these were run the Jewish teachings. We have thus a peculiar combination – the religious doctrines of the Bible, as culminating in the person of Jesus, run through the forms of an alien philosophy.

The Doctrine of the Trinity. The Jewish sources furnished the terms Father, Son and Spirit. Jesus seldom employed the last term and Paul’s use of it is not altogether clear. Already in Jewish literature it had been all but personified (Cf. the Wisdom of Solomon). Thus the material is Jewish, though already doubtless modified by Greek influence: but the problem is Greek; it is not primarily ethical nor even religious, but it is metaphysical. What is the ontological relationship between these three factors? The answer of the Church is given in the Nicene formula, which is characteristically Greek, . . .

Also significant in this connection are the following passages of another article in Encyclopaedia Britannica (xiv edition), entitled ‘Church History’: The recognition of Christ as the incarnation of the Logos was practically universal before the close of the 3rd century, but His deity was still widely denied, and the Arian controversy which distracted the Church of the 4th century concerned the latter question. At the Council of Nicaea in 325 the deity of Christ received official sanction and was given formulation in the original Nicene Creed. Controversy continued for some time, but finally the Nicene decision was recognised both in East and West as the only orthodox faith. The deity of the Son was believed to carry with it that of the Spirit, who was associated with Father and Son in the baptismal formula and in the current symbols, and so the victory of the Nicene Christology meant the recognition of the doctrine of Trinity as part of the orthodox faith. The assertion of the deity of the Son incarnate in Christ raised another problem which constituted the subject of dispute in the Christological controversies of the 4th and following centuries. What is the relation of the divine and human natures in Christ? At the Council of Chalcedon in 451 it was declared that in the person of Christ are united two complete natures, divine and human, which retain after the union all their properties unchanged. This was supplemented at the 3rd Council of Constantinople in 680 by the statement that each of the natures contains a will, so that Christ possesses two wills. The Western Church accepted the decisions of Nicaea, Chalcedon and Constantinople, and so the doctrines of the Trinity and of the two natures in Christ were handed down as orthodox dogma in West as well as East.

Meanwhile in the Western Church the subject of sin and grace, and the relation of divine and human activity in salvation, received special attention; and finally, at the 2nd Council of Orange in 529, after both Pelagianism and semi-Pelagianism had been epudiated, a moderate form of Augustinianism was adopted, involving the theory that every man as a result of the Fall is in such a condition that he can take no steps in the direction of salvation until he has been renewed by the divine grace given in baptism, and that he cannot continue in the good thus begun except by the constant assistance of that grace, which is mediated only by the Catholic Church.

It is evident from these statements of Christian scholars that it was exaggerated love and veneration of Christ which led the early Christians astray. This exaggeration and the use of expressions such as ‘Lord’ and ‘Son of God’ led to Jesus being invested with divine attributes and to the peculiar Christian notion of redemption, even though these could not be accommodated into the body of the teachings of Christ. When the Christians came to be infected with philosophical doctrines, they did not abandon the original error into which they had fallen, but tried to accommodate the errors of their predecessors through apologetics and rational explanations. Thus, instead of returning to the true teachings of Christ, they used logic and philosophy to fabricate one false doctrine after another. It is to this error that the Qur’an calls the Christians’ attention in these verses.

For a faster and smoother experience,

install our mobile app now.

Related Ayat(Verses)/Topics